In April 2020, a forty-year-old woman admitted herself to hospital in Ontario, Canada. Straight away, the doctors treating her were convinced she had Covid-19. She had all the classic symptoms: a fever, chills, a cough, shortness of breath and she required oxygen. Then her test result came back. It was negative. This struck her doctor, Brandon Budhram, as odd. The woman worked in a long-term care facility where cases of the disease were spiking. She was exactly the kind of person you would expect to contract Covid-19. Shrugging off their doubts, Budhram and his colleagues continued to work off the assumption that she had the virus.

The patient stayed in the hospital for a few days, where she had a series of tests: X-rays, a CAT scan, a blood test. “It all looked like it would be compatible with Covid-19,” Budhram says. Three times during her hospital stay the woman was tested for the disease. Each time the result came back negative. Undeterred, her doctors continued to treat the woman as if she had Covid-19. “We were still in the back of our heads thinking, you know, this sounds like it probably is Covid” says Budhram.

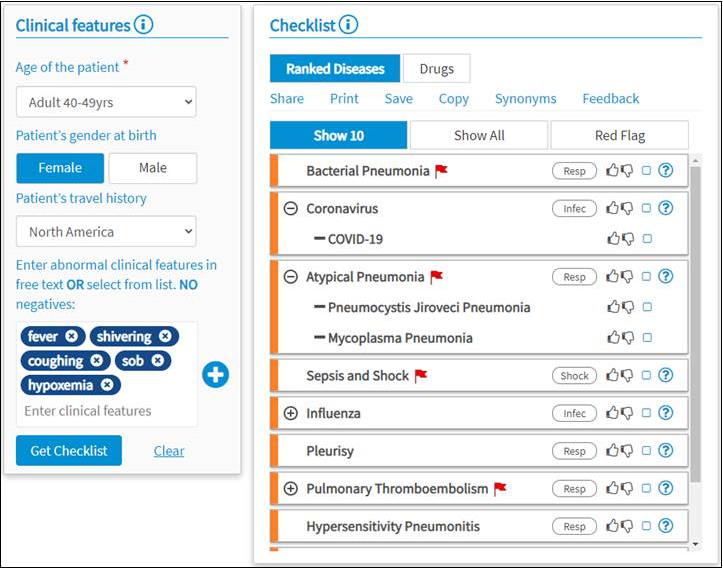

A week into her hospital stay, the patient requested to be discharged, but before she left, Budhram and his colleagues ordered a bronchoscopy, a procedure which offers a peek into the inner portions of the lungs to see what's going on. The bronchoscopy didn’t show any signs of Covid-19, but it did find something else: Pneumocystis jiroveci, a fungal infection often found in people infected with HIV. “Our whole mindset switched,” says Budhram. The doctors called her back in, and they soon found more signs of HIV infection they'd missed when the patient was admitted: a skin lesion, an active genital herpes infection and a reported fifty-pound weight loss over the past year. A test for HIV infection came back positive immediately. “We could have easily missed that completely,” says Budhram. The woman began treatment, and within a few weeks, she had improved significantly. “Looking back, this is the most classic, obvious case of AIDS I’ve ever seen in my life,” he says, “and one year ago, I would have picked that up, no problem.”

If he had managed to miss one diagnosis, Budhram wondered how many other doctors were also misdiagnosing patients as having Covid-19. With his colleague Alex Kobza, he wrote a case report about his misdiagnoses and other doctors began to get in touch, saying they had experienced the same thing, with mistakes even worse than his own, such as missed heart attacks. “It’s a universal thing,” Budhram says.

In those early, nightmarish, days of the pandemic, uncertainty was rife. Doctors knew so little about this novel disease, new scientific literature was being pumped out every day, hospital protocols were constantly fluctuating – they were, by and large, having to improvise on the fly. In amongst all the immediate tragedy of the pandemic, Budhram started wondering how often he and other doctors were getting things wrong. How many cases were being missed because doctors were on the lookout for Covid-19? And how could he stop it happening again?

Diagnostics is an imperfect art at the best of times. A 2017 study of patients in the US found that more than 20 per cent of patients with serious conditions who sought a second opinion had been initially misdiagnosed by their primary care providers. In the US, an estimated 12 million people are on the receiving end of diagnostic errors every year. A portion of these mistakes, although an exact number is difficult to determine, are thought to be caused by what are called cognitive biases, the preconceived notions hardwired into our brains with an annoying tendency to cloud our judgment. Humans – even doctors – are far from the coolly rational decision-making machines we might like to think of ourselves of. Add in the chaos of a pandemic, and the gaps in our reasoning suddenly start to open wide.

Take a doctor who has spent weeks on the Covid-19 wards, in a city where cases are spiking. They see a patient with similar symptoms to Covid-19, and chances are it’ll be the first diagnosis that jumps to mind. Psychologists call this availability bias, the tendency to judge diagnoses as more or less likely depending on how easily they come to mind, and in the midst of a pandemic, Covid-19 has become permanently emblazoned at the forefront of medics’ brains. Some misdiagnoses could be attributable to anchoring bias too, where people rely too heavily on an initial piece of information in making subsequent judgments. A doctor sees a patient coughing, with a tight chest and a high temperature – how could they not immediately think Covid-19?

There are multiple examples of cases over the past year where patients were incorrectly thought to have Covid-19. Sometimes the consequences were fatal.

Full story can be found here - Doctors were sure they had Covid-19. The reality was worse | WIRED UK